No More Heroes

by Bridget Wilkins

Why is design history so obsessed by appearance?

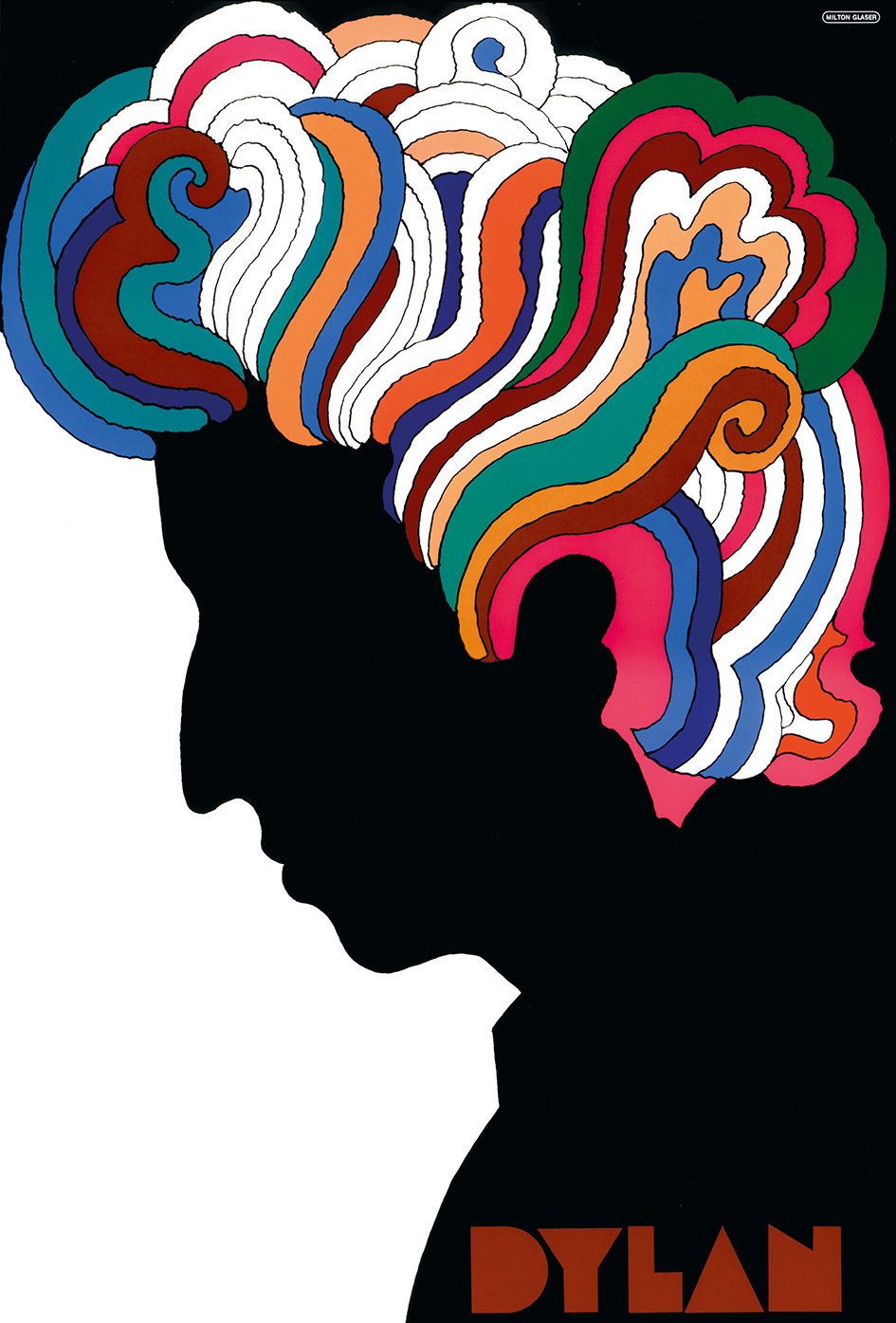

It is taken for granted that graphic designers will be familiar with the history of the discipline and that they will know what Milton Glaser’s posters or Herbert Bayer’s typography look like. But how does this ‘look’ inform or help us, apart from functioning as a ‘naming of the parts’, or as a store of outdated visual clichés? Why do we need it, and do we even need it? Is it time to question what kind of history is actually being fed to us?

Old-fashioned approaches

At present, graphic design history is modelled on the earliest approaches to art history.On the one hand there is the ‘hero’ approach, which singles out individuals and emphasises the designer not as a communicator but as a personality. Life stories and anecdotes predominate; presented in a linear way, form birth to education to eventual maturity.On the other hand, there are the stylistic and thematic approaches. These treat categories such as ‘corporate identity’ or ‘New Wave’ in a similarly linear fashion, progressing from the earliest examples to the most recent, and encouraging us to classify objects and images as though they were universal and indefinitely fixed.

These linear concepts of history are ignoring some of the central issues in graphic design. The discipline is defined by the technological limits of the time in which the design is made, as well as the motives and ambitions of the commissioning agent – and these factors need a much closer analysis. But, above all, it is to do with communication. The strangest aspect of graphic design history as it is presently written about, taught and discussed is the almost total absence of discussion about the way in which these communications are received by their audiences.

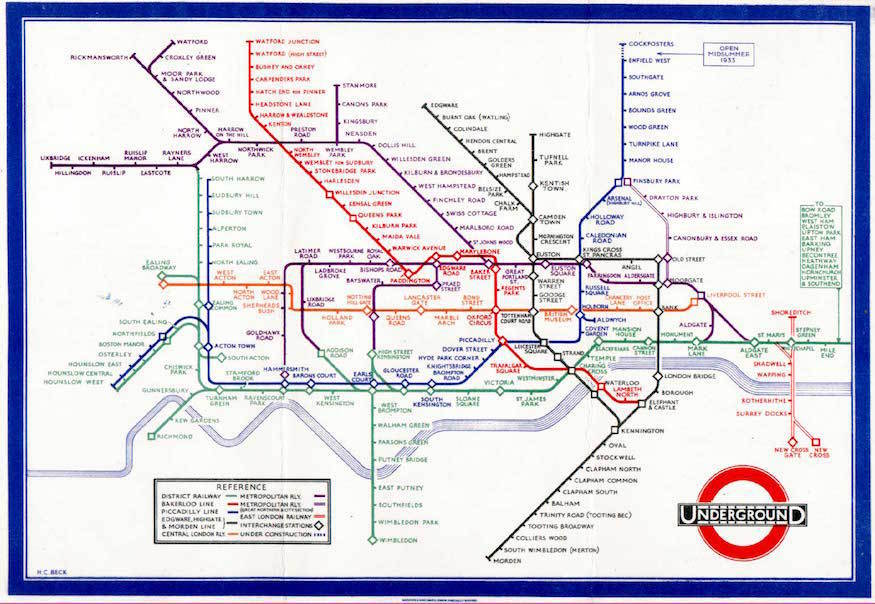

Did grandma find the geographical distortions of the London Underground map (1931) confusing because they were so modern and unfamiliar? Such questions are rarely asked. But it is only with the inclusion of this normally absent context that there can be meaningful and constructive comprehension of history.

Contextual criticism

Compared with other areas of design, graphic design has been given short shrift by historians. In recent years much attention has been devoted to consumer and household designs and the circumstances surrounding their production and consumption, with a spate of books and exhibitions on the subjects of chairs, cars, hoovers and living-room decor. These studies are less concerned with the analysis of visual style than with the consideration of the context in which the design was produced. One such book, Adrian Forty’s Objects of Desire: Design and Society 1750-1980, analyses the ways in which patterns of consumption dictated the form of transport, typewriters and appliances.

How far could such an approach be applied to graphic design history? On the whole, graphic design does not fit the same categories of consumption as fridges, hoovers, and so on. Most graphic design – shopping bags, bank leaflets, company logos – is not an ‘object of desire’, although some might put such things as album covers and style magazines in this class. Most of it is ephemeral. Much of it is locked into a particular time and place and loses its relevance once the moment has passed. Often it is not purchased or consumed in an active sense so much as received – like a telephone directory, street poster or stamp. The graphics, if they are consciously noticed at all, have only secondary significance.

Material values

For these reasons, the status of graphic design (and graphic designers) is quite low in the hierarchy of design. The objects do not have the same material value, are not as collectable and do not have the same display potential as three-dimensional forms of design. Of course, books, posters and album covers are collected, displayed in the home and treasured for their nostalgic qualities, but in the museums they are not big crowd-pullers compared to the other applied arts. Those items that are regarded as display-worthy are selected not be consumers but by self-appointed arbiters of taste, such as exhibition curators, collectors and historians. What criteria have they used in this selection? I suspect that it is those that look punchiest, or will come across well when reduced and reproduced in the pages of books and magazines, where the same old chestnuts appear again and again.

But the fact that so much has already been discarded could work to the advantage of graphic design history. It means that the still emerging discipline is not wholly saturated with the superficial coverage some areas of art and design have received. And it creates a space in which a new, more meaningful approach to history could be developed. This still begs the question: what is the most appropriate approach?

On the occasions when two-dimensional design is displayed in museums – as, for instance, at the Bodoni Museum in Parma, Italy – history is presented in terms of objects (books, punches and matrices) in isolation, as exotic specimens caught under glass. This allows us to admire them as artefacts, but it tells us nothing of the way in which they came to be created, or how people received and evaluated them at the time of production (or later).

Designed for life

Graphic design remains arguably the most immediate and instantaneously arresting of the design disciplines. We need to capitalise on this and use it to relate the objects to their context in a meaningful way. If most graphic design is seen, used and owned by the public, why should it not have a lively history that constructively explores and communicates its qualities? Everyone uses letters, words and imagery. Everyone has a view of the redesign of their daily newspaper, or the appropriateness of using a newborn baby, or someone suffering from HIV/AIDS.

We need to explain not ‘what it looks like’ but ‘why it looks the way it does’, how a piece of graphic design communicated and to whom.

We should not allow a preoccupation with financial and aesthetic value to blind us to the historical value of all graphic ephemera. A wartime ration book has as much to tell us about communication design, people’s daily experience and society in the Second World War – in other words, graphic design history – as a poster by Abram Games. The danger of graphic design hierarchies, museum collections of acknowledged ‘classics’, and the hero approach is that they prevent us from seeing this. An excessive concentration on the look of a piece of graphics also ignores the fact that we live in multicultural societies and that visual images are understood by different cultures in different ways.

If graphic designs are to communicate effectively in the future, it is essential to examine issues deeper and wider than the purely visual. What better way to start than by addressing your own history in this way?

Bridget Wilkins, design historian, London, Spring 1992